Rejection: It Hurts

For the love of God please do not call me resilient for writing this. Don’t call me brave.

Resiliency, Google tells me, is the capacity to withstand or recover quickly from difficulties. And I suppose writing nonfiction is an act of bravery, but I tire of the word, tire of reading it on the book jackets of all the memoirs I love. To me the word has become oversaturated. Its lost its meaning. Writing what I write— mostly personal creative nonfiction— involves a constant reckoning with your self, your past, and what you may have gotten wrong/still be getting wrong. It sometimes involves digging, sometimes obsessive digging, a never-ending question that often, instead of getting answered, morphs into a bigger, more unsettling question. For me each essay I write, be it about my father and his drinking or a sexual assault I experienced, the gold thread of the piece is always, always about my self and my relation to the world around me. I’m not sure if that’s brave; in fact, oftentimes, it feels selfish, narcisstic, delusional. I remember an early nonfiction writing workshop in which I first submitted an essay about my father and his alcoholism, remnants of which now exist in my finished manuscript. Someone in that workshop, when it came time to give feedback, said: I wish I had something interesting happen to me so that I’d know what to write about. As if inherited familial trauma is a gift.

I want to tell you that throughout the last decade of writing this now finished book I have doubted myself, my writing capabilities, my place in the publishing writing world, my family’s belief in me, my worth. I questioned if the story of my father and his father and the crime that united them was my story to tell; I wrestled with a sense of guilt and shame after almost every sentence I wrote. My place in my small family was always one of ‘otherness,’ and I constantly feared (still fear) what this book will do to that conception. I don’t know if I’d call it brave that I kept going, that I wrote until the word count hit 40,000 and then went on writing still. I don’t know if it’s resilient that I kept going with this project, one so personal and heavy, instead of turning to fiction, a novel I’ve been imagining for a year now or some other imagined landscape.

I see resilience in my sister-in-law. She’s pregnant for the first time and due to a serious blood clotting issue in her pre-pregnant life, she has to give herself injections in her stomach every day to prevent potential clots to the fetus. Her round tummy is punctuated with bruises of all shades, green and purple and brown and black. I know it must be painful; does she feel an ache when I place my cupped hand over her hard stomach? It’s resilient that she doesn’t ask me not to hold her stomach; it’s resilient that she still feels excited about pregnancy.

Why do I write nonfiction? I don’t know. I suppose it has to do with being the black sheep of the family growing up, maybe the black sheep of my entire town (that’s what it felt like then, anyway). I was laughed at and mocked for my dedication to books and art, in the way many in small towns are. I was popular but within the popular circles I was outcasted. Maybe all those journals I filled with my fast, anxious thoughts evolved into this writing of life. Specifically I think this manuscript, this memoir-in-essays about my father, his father, and me, has possessed me. I’ve poured hours into archival research; I’ve paid for newspaper.org subscriptions in an attempt to hunt down otherwise lost information; I’ve Googled names to see if witnesses and judges and jurors are still alive. At first the impetus was to find answers to my questions: where did my father’s alcoholism originate? What really happened in that farmhouse in 1966 when my father was six years old? Are the two connected, the crime and the alcoholism, and if so, how? But the actual act of writing the book led to different questions, questions about my self and where I’ve mis-stepped, where I’ve assumed things I shouldn’t have. I’ve learned that I do not want to be the person cataloguing their life in the form of an ongoing essay. I don’t want to seek out experiences for content, for metaphor making.

If there’s any part of my writing that I’d label brave it’s the part that involves telling people. In March of this year I began querying literary agents to hopefully achieve representation for my memoir-in-essays. Querying is an exhausting process; depending on what a specific agent wants, you may be required to provide a full manuscript or sell them on only ten short pages. Sometimes you’re required to send a synopsis, a table of contents, a market analysis, a comparative title analysis. A lot of times agents close their submissions, or are only open to referrals (i.e. those coming from an MFA program or those who are friends with already established writers). In 2020 I also queried agents— I heard nothing back and I hardly told anyone I had tried. This year, though, I feel like I know my book much more. I’m confident in what the book is, what it’s trying to achieve. Querying, therefore, felt better, although it was still tiring, frustrating, and sometimes soul-sucking. I’ve queried almost thirty agents since March— three have responded with gracious nos, one responded asking for my entire manuscript (a great sign!), and the rest have yet to respond. They may not ever respond. I’m also, in the midst of this search, still submitting individual essays out for publication to literary magazines. And I’m working full-time. The amount of rejection in my inbox is astounding. It’s not the fact that I keep submitting, keep querying, that feels brave to me. I feel brave telling people that I’m seeking an agent, that I’m working so hard for it. I feel brave posting on Instagram about it, even if it’s only to my ‘close friends’. I feel brave talking to people about the contents of my book, finally.

I always thought that not telling people, not letting them in to this hard work, would protect me from the pain of rejection. I’m realizing, as I write this, that I am motivated by shame and embarrassment. I fear telling others what I’m doing because then I’ll have to tell them when I fail. Anxiety functions this way for me: I’d rather protect myself in attempts to reduce the sting of future heartache. But sharing has felt so incredibly good because it shows me that people are interested. I have readers, readers who care about what I’m doing, what I’m working on, what’s coming next. I have people from all corners of my life rooting for me, cheering me on. Had I not opened up to them about the full manuscript request from that one agent I don’t think I would have felt as proud as I did, as celebratory. Their reactions reminded me of how huge of a step I’d made in this terribly tough world of publishing. They reminded me that I was doing it. I was writing, I was inching toward becoming a Writer.

The back of a Lyft at 8AM. Returning from LAX after a long, uncomfortable Spirit Airlines flight from Cleveland. An email comes through, one I’ve been waiting on for nearly two and a half months. The agent. The one I dreamed about calling MY agent.

Her answer is your writing is beautiful, your project is important, but. Her answer is a clear editorial vision is crucial to a memoir and I don’t have that. Her answer is no. Her answer is please consider me for future work but I can’t read or feel anything but the no. Her answer is no.

We flew to Ohio to visit family on a Friday and flew back that Monday. On Friday night and Saturday morning my husband and I stayed with our friends in their beautiful house purchased in Shaker Heights, a suburb of Cleveland. The four of us drank coffee and ate breakfast sandwiches, and we joked about the two of them selling us on moving to Cleveland. On the hour long drive to Canton after we left them my husband and I thought independently about the possibility, yet again. It’s tempting, the size of these houses and yards, the quiet, open green spaces, the lack of traffic. On Saturday afternoon we thought maybe. For not the first time we thought perhaps.

And then we attended a wedding where my husband was the only person of color in attendance. We were stared at with laser vision. My husband and I left after dinner and I drove him to the Bolivar Dam, a place of importance in my book and in my life: it’s where I learned how to ride a bike with my dad. We decided that to erase the weirdness of the wedding we’d go to the drive-in a half hour south of my hometown; my husband had never experienced a drive-in and he was giddy that for $7 a piece we could watch two movies while cuddling in the grass.

The Flash started playing on screen. Outside of the car beside us was a family of four; their older boy, maybe ten years old, seemed excited for the superhero movie. But suddenly my husband told me to listen to what the boy was saying every time the movie’s main actor (Ezra Miller) came on screen. I didn’t want to hear what I was hearing but there it was, clear as day. The kid was saying, over and over again, “I don’t like this Asian superhero ripoff.” At one point, when a shaken beer explodes on Ezra Miller’s face, the kid shouted ‘that’s how Asians drink their beer!’ (what does that even mean???). We sat there listening to this kid hurl microaggressions into the air in both disbelief and familiar knowing. It was dark and the kid probably didn’t see my husband. His parents remained silent, letting him continue bitching about the Asian superhero (who isn’t even Asian, lol).

As I listened my anger flipped around and around inside of my chest. I told my husband we needed to get off the ground and into the car. At one point I considered saying something to the kid’s parents but I knew my involvement would make the situation feel worse for my husband, the actual person hurt by what was happening. We got into the car, both of us defeated and sad, and waited for the movie to end.

The next day, when my parents asked how the drive-in was, I told them it was fine. I did not want my husband to labor by explaining to them what happened, why it hurt. Later, when we congregated as a family around my brother’s pool, as we tanned in the sunshine and bright blue of an Ohio summer, my friends asked us why we wouldn’t just move back, asked us ‘isn’t this nice? don’t you want this?’ It was nice, beautiful even. How unfair, this beauty we didn’t feel safe in.

I felt incredibly isolated in that moment, in the moments since. How to explain what happened at the drive-in? How to explain how painful it is to be the only Asian in the crowd? My husband grew up in a town where he was often the only person of color there— I never want him to have to experience all of the microaggressions that come with that again. And I’m not stupid enough to believe this kind of stuff doesn’t happen in Los Angeles or other major cities: it does. But having representation, in people, food, culture, makes a difference. It means kids will be more familiar with what being an Asian person is; it means they won’t feel so confident screaming about what a disappointment an Asian superhero is.

Maybe my parents and friends would get it, but I’m tired just of thinking about this talk. I don’t want to be told to brush it off, that some people suck but not all. One of the major reasons I left in the first place is because of how insidious the racism is there. How easy it is for people to say things without repercussion, without anyone correcting them. Growing up I had one Asian friend who was half-Korean; when she came over my dad nicknamed her the Angry Asian because she was so often pissed off and irritated. He loved my friend and still asks about her, not by her name but by this nickname he thinks is endearing. I spent that Saturday night after the drive-in picking my cuticles with regret that I didn’t try harder to correct my father when he first named her that, when he continued calling her that.

Is it resilience for people of color to withstand such bullshit? Is it resilient that they continue living in these places despite? Why are the places where people of color feel the safest the most expensive in the country? Why isn’t my husband— and by extension me and my future children— welcome in the beauty of an Ohio sunset?

We left Ohio this trip with an absolute answer for the question of if we could live there. No, we cannot. I have not, in my eight years of knowing my husband, ever seen him so affected by a situation like this before. I can’t guarantee that he won’t experience something like this again but I’ll be damned if I purposefully put him in front of it by moving to a place like this.

I was so exhausted and battered on that Lyft ride back from LAX, so emotionally devastated and lonely. I knew my husband was also upset, lonely, grieving a future he had again begun to imagine. I know he felt sad thinking again about how expensive life would be if we stayed in LA; I know he worried about how to make it work, now that we knew definitively nowhere else would work. And I read the no from the agent within that cyclone of emotion. It felt like a double shot of rejection— my hometown did not want me and neither did the agent. I didn’t belong there and my book didn’t belong with her.

That entire day I cried. I sat at a park and cried heaving sobs into my cardigan. I cried until I was delirious with exhaustion, the cry of having just been dumped. My heartbreak felt tender and impossible to write about, impossible to tell anyone about. I showed my husband the email in the backseat of the Lyft and at first thought I wouldn’t tell another person.

But I did tell people, the ones I’ve let in in my personal life about the book and the querying journey. I texted them the email screenshot and thanked them for their support. And now, only two days after reading that email, I’m telling you all about the rejection. On Monday it felt impossible that I’d open up the word doc of my manuscript again or that I’d start the agent-hunt over again; but today I have eighteen tabs open on my laptop full of agents. Today I responded to the agent who said ‘thanks but no’ and told her I have a novel I’d like to run by her some time in the future.

My husband told me this rejection hurts so badly because it’s so close. It’s a higher-level rejection, which means I again have to confront the imposter syndrome sitting in my gut. I’ve conquered (kind of?) the imposter syndrome of submitting to lit mags, but this new level still feels frightening and not mine to claim.

It fucking sucks to be rejected. It hurts. In the hours after reading that email my brain ran through 405845976 questions, all of which put into doubt my writing quality, my book’s worth. All I could do was sit with those questions, some of which were valid and some of which were mean and cruel, anxiety’s attack on my wellbeing. All I could do was listen to the people I shared with and trust that what they were saying was true: I had to keep going. I had to keep believing. My work was good.

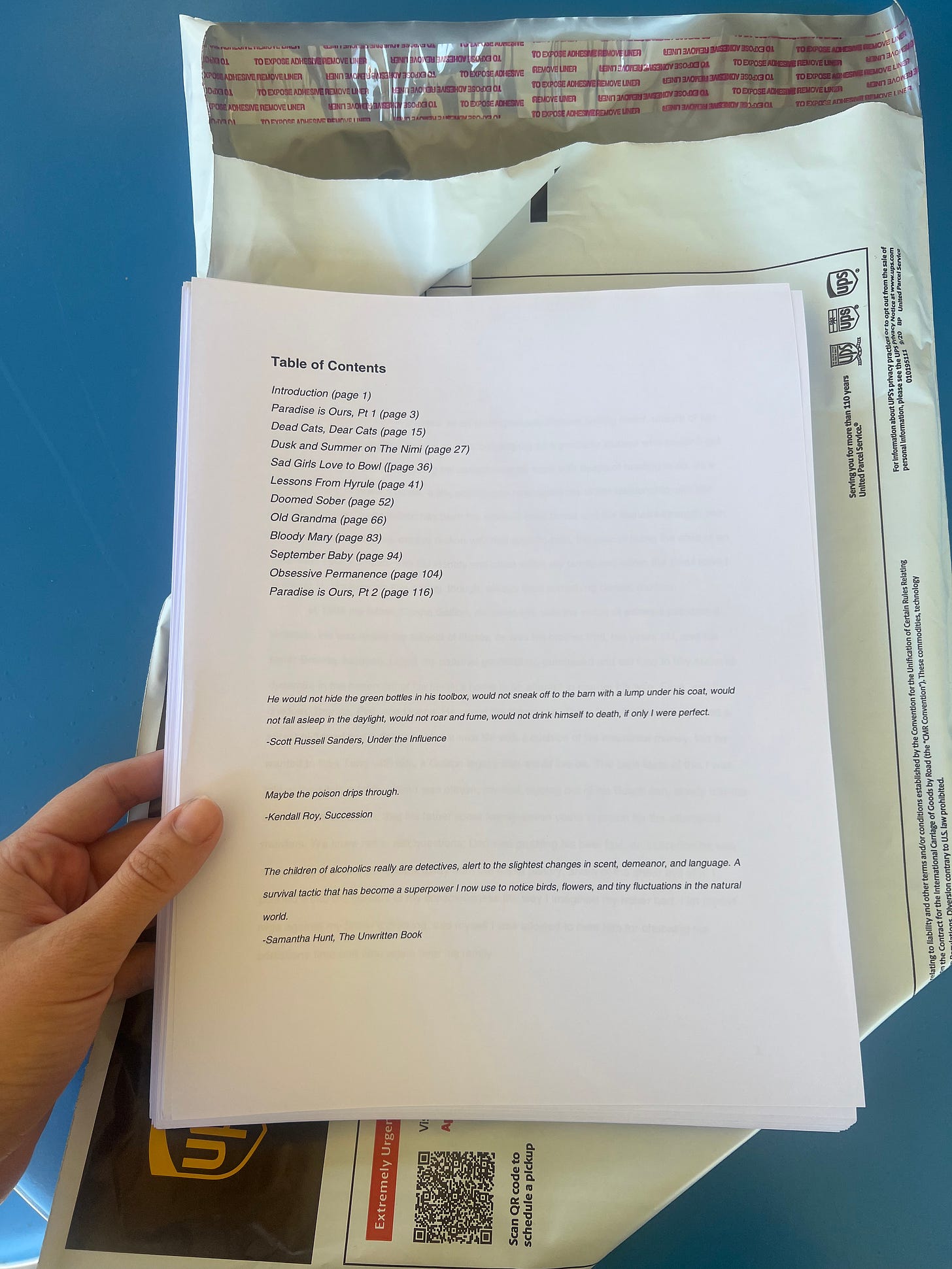

Last week, still waiting for the agent to respond to my full manuscript, I decided to print out my book. It was the first time I saw my words printed out altogether and the mass of paper amazed me. I did that, I thought, watching it print and print and print. As I waited for the printing to stop I surprised myself by telling the man working there: this is my first book. He responded with a wow and a congratulations; when he handed me my thick packet of papers I smiled and held back a cry.

I wrote a fucking book. I married a fucking amazing man. I don’t know if either of those things are brave or resilient. But I know I’m proud.

Such beautiful writing Erika. So many emotions and thoughts I have, I’ve read it twice and likely will keep coming back. I am one of your readers for life friend 🫶🏼

Every time I end up in rural Ohio, I am reminded why I left. This made me so angry.